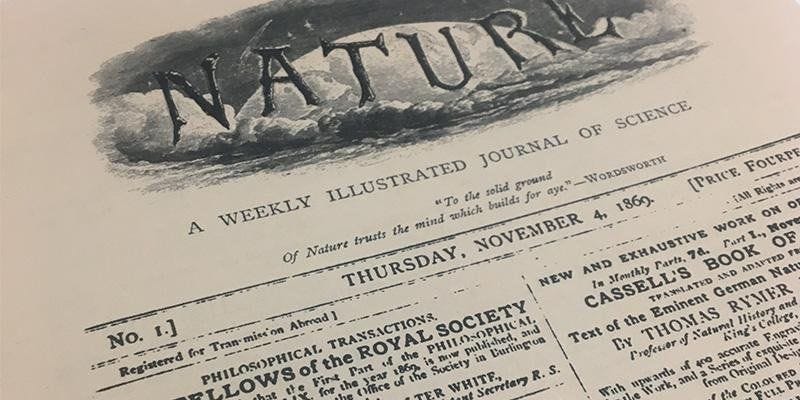

The history of scientific publishing (II)

An accusation of corruption was the main trigger of peer review process as we know today

As I described in my last post, the present-day peer-review system evolved from 18th-century, began to involve external reviewers in the mid-19th-century, and did not become commonplace until the mid-20th-century.

Peer review became a touchstone of the scientific method, but until the end of the 19th century was often performed directly by an editor-in-chief or editorial committee. Editors of scientific journals at that time made publication decisions without seeking outside input, i.e. an external panel of reviewers, giving established authors latitude in their journalistic discretion. For example, Albert Einstein's four revolutionary Annus Mirabilis papers in the 1905 issue of Annalen der Physik were evaluated by the journal's editor-in-chief, Max Planck, and its co-editor, Wilhelm Wien, both future Nobel prize winners and together experts on the topics of these papers. On a much later occasion, Einstein was severely critical of the external review process, saying that he had not authorized the editor in chief to show his manuscript "to specialists before it is printed", and informing him that he would "publish the paper elsewhere" – which he did, with substantial modifications.

While some medical journals started to systematically appoint external reviewers, it is only since the middle of the 20th century that this practice has spread widely and that external reviewers have been given some visibility within academic journals, including being thanked by authors and editors. What happened? Let’s continue detailing the history.

Journals were not the only institutions meant to evaluate the quality of science. At funding bodies, external refereeing of grant proposals was quite rare prior to World War II. Private grant organizations such as the Rockefeller Foundation, for example, generally left funding decisions in the hands of their employees, who were trusted to evaluate a scientist’s worthiness for a grant internally whether or not they understood the science at stake. Grant organizations associated with governments or scientific societies were more likely to use external refereeing, although the practice was by no means universal.

Journals and funding bodies both began placing more emphasis on external refereeing following the Second World War. One reason for the shift towards refereeing at journals was the increasing burden on editors as the number of scientists—and scientific papers—expanded due to generous Cold War funding. Although in the beginning of the century, the journals did all refereeing tasks in-house, in the 1950s, members of the editorial board of American weekly Science complained that “the job of refereeing and suggesting revisions for hundreds of technical papers is neither the best use of their time nor pleasant, satisfying work,” and agreed to begin sending papers to outside experts. Similarly, when the American Journal of Medicine was founded in 1946, its editor Alexander Gutman wanted to offer his authors fast publication (does it sound familiar to you today?) and decided to handle acceptances and rejections almost entirely on his own. However, as the journal became more popular, Gutman was unable to keep up with the number of submissions, and by the 1960s he too had begun sending papers out for external opinions.

But the growing workload at scientific journals does not explain how refereeing became crucial to the very idea of scientific rigor. The link between refereeing and scientific legitimacy seems to have followed the dramatic rise in government-sponsored research in the postwar United States. Between 1948 and 1953, federal spending on scientific research in the US increased by a factor of 25. The massive expansion of government funding led to more public attention on scientists—and to suggestions that science should be more accountable to the public and to members of the US Congress. Scientists, on the other hand, were less than enthusiastic about the idea that their grant proposals should be evaluated by laymen with no scientific training.

The tension between accountability to the public and scientific autonomy raised to its peak in the mid-1970s during a controversy over research grants awarded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The early 1970s were a time of growing economic crisis for the US, and three legislators—Republican Congressmen John Conlan and Robert Bauman , and Democratic Senator William Proxmire —launched a series of very public attacks on specific grants the NSF had awarded. The three men accused the NSF of awarding frivolous grants—largely in the social sciences—and wasting taxpayer money on projects such as a middle-school sociology curriculum and a study of stress in rats and monkeys. Bauman and Proxmire argued that the NSF’s poor decision-making justified far more Congressional control over the grants they awarded. Don’t think of any scientific new current: all was about the political campaing that Jimmy Carter (who became president in 1976) deployed against many institutions in Washington.

By this time, referees for journals and for the few funding bodies who used them systematically had grown to expect that their identities would remain a secret from the authors, and NSF Director H. Guyford Stever cast Conlan’s request as a major break with scientific protocol. Interestingly, the mid-1970s were also the moment when Americans increasingly called refereeing by a new term: “peer review.”

Probably, the rest of the story is more well-known for the current readers, and many of them will know about the secretive peer review process that is carried out today for publishing a research article in any journal, or achieving a grant. However, the perverse creation of H-index as one of the worst ideas for measuring the scientific performance, the proliferation of predatory journals, the raise of the fees for publishing and the difficulties for experiments replicability have turned this activity into a madness, and have led to lose most of their rigour and prestige even among scientists and society.

ChatGPT and its ability to create long natural sounding texts about any scientific topic has brought the last bad news to this world, and here are just some links to ones of the biggest symptoms of an agonizing publish or perish system that it’s about to suffer a big implosion, hopefully:

How many academic papers are written with the help of ChatGPT?

Many are using LLMs to replace humans (researchers and participants) in research and development.

The Google scholar experiment: How to index false papers and manipulate bibliometric indicators.

U.K.-based staff at Springer Nature, publisher of Nature and hundreds of other scientific journals go on strike over a dispute about pay.

References

[2] Enclyclopedia of the history of science. Carnegie Mellon.

[3] The Rise of Peer Review: Melinda Baldwin on the History of Refereeing.

[5] Wikipedia