The history of scientific publishing (I)

The process of peer-reviewing and the publish or perish.

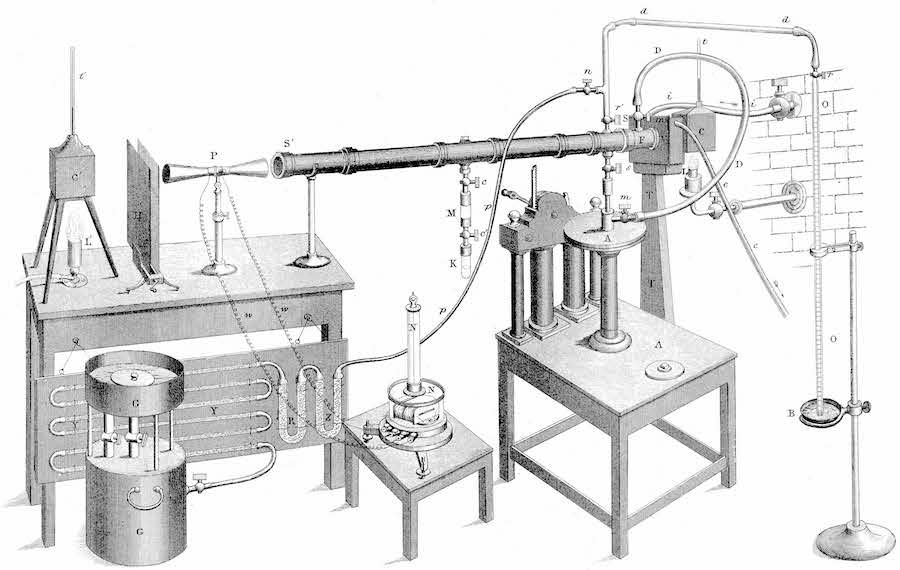

In January 1861 John Tyndall, a physicist at London’s Royal Institution, submitted a paper to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. The paper bore the title “On the absorption and radiation of heat by gases and vapours, and on the physical connexion of radiation, absorption, and conduction.” After testing the heat-retaining properties of several gases, Tyndall had concluded that some were capable of trapping heat, and thus he became one of the first physicists to recognize and describe that basis for the greenhouse effect. A month after its submission, the paper was read aloud at a meeting of the society, and several months after that, a revised version of the paper was in print.

This process of scientific publishing will sound familiar to modern scientists. However, Tyndall’s experience with the Philosophical Transactions—in particular, with its refereeing system—was quite different from what authors experience today. Tracing “On the absorption and radiation of heat” through the Royal Society’s editorial process highlights how one of the world’s most established refereeing systems worked in the 1860s. Rather than relying on cold anonymous referee reports to improve their papers, authors exchanged extensive personal letters with their reviewers.

Refereeing was not typical for scientific journals in 1861. Many commercial scientific publications, including Nature and Philosophical Magazine, accepted articles with little or no outside refereeing, and most journals on the European continent relied on the judgment of highly qualified editors to determine what would be accepted or rejected. British scientific societies often employed opinions from other experts in the paper’s field.

Papers submitted to the Transactions were routed to one of the society’s two secretaries, the de facto editors of the publication. These secretaries were eminent researchers who arranged refereeing and provided their own expert judgment on papers submitted for publication. One secretary handled the biological sciences, the other the physical sciences.

Earlier, in 1665 the Royal Society gave its secretary Henry Oldenburg permission to compile Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, generally regarded as the world’s first scientific journal. Oldenburg immediately thought it wise to gather this kind of expert opinions on the papers he wanted to publish.

Although Oldenburg was indeed a pivotal figure in the history of science publishing, he was not peer review’s inventor. That honor arguably belongs to William Whewell, a Cambridge University polymath who also coined the terms “physicist” and “scientist.” In 1831 Whewell suggested that the Royal Society should commission written reports on papers submitted for publication in Philosophical Transactions. He thought those reports should then be published in the Society’s new journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, thereby fulfilling the dual purpose of fostering rich scientific discussions and providing material for the new publication.

The Royal Society adopted Whewell’s suggestion of soliciting reports but shifted quickly away from his vision of printing them for public discussion. A handful of reports did appear in Proceedings, but by the mid 1830s that practice had ceased. Instead, the society decided that referee opinions were mainly useful for helping it avoid printing anything embarrassing in its publications. By the mid 19th century, refereeing for Philosophical Transactions was almost entirely run by two secretaries, one in the physical sciences and one in the biological sciences (the ones that we mentioned in the case of Tyndall), as we’ll see in next paragraphs.

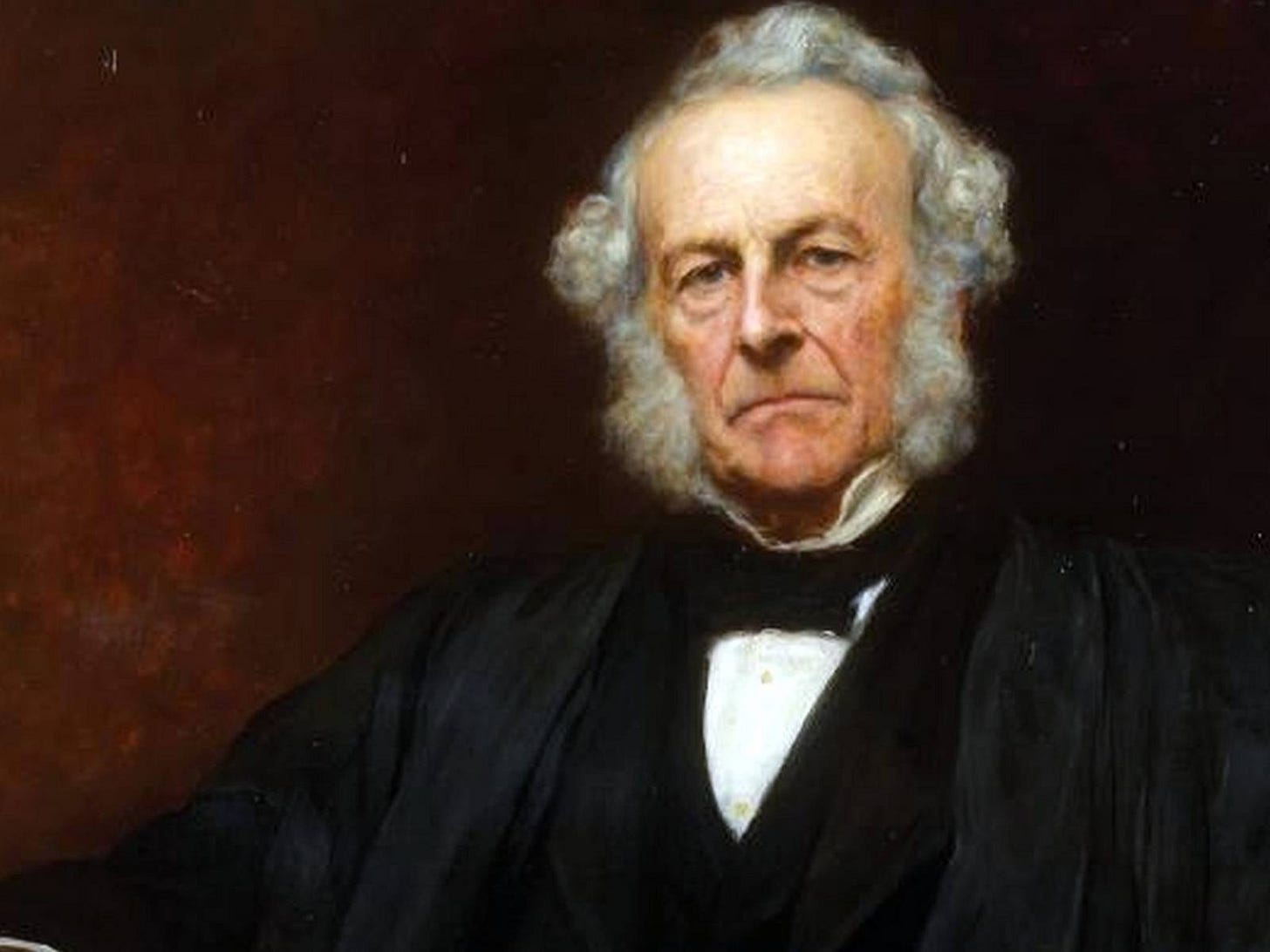

George Gabriel Stokes

In 1861 the physical sciences secretary was George Gabriel Stokes, one of the most respected physicists in Victorian Britain. I’m sure that many of my readers will have heard about the Navier-Stokes equations to model the turbulent regime gases. He held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge and made meaningful contributions to research on fluid dynamics and light. He was also a significant figure in the history of refereeing. When Stokes began his tenure as secretary in 1854, the Royal Society was still reeling from an intense public controversy about favoritism at the Transactions. To address such concerns, Stokes took on the task of standardizing refereeing for Transactions papers.

After receiving “On the absorption and radiation of heat”, Stokes arranged for two experts to review the paper. One was his closest friend, William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), arguably the most important physicist in Britain. The other referee was Stokes himself. This was not unusual; Stokes had wide-ranging knowledge of physics research and often refereed papers in the physical sciences.

After a few weeks, Thomson returned a referee report to the Committee on Papers, the Royal Society group that made final decisions on which papers would be accepted. That report has unfortunately not survived, though Thomson’s correspondence with Stokes suggests that he recommended publication.

Stokes, on the other hand, did not file a formal report with the society. In a letter to Thomson, he mentioned that he

“did not write a report on Tyndall’s paper but merely recommended it.”

Although he told the committee that he disagreed with Tyndall’s conclusions about the relationship between conduction and radiation, he said that:

“if the author wished it retained he had done such good work that he had, I thought, a right to keep it.”

Stokes could make a verbal report to the committee in part because the referee reports, at that time, were not shared with authors—they were meant to inform the committee’s decision, not to help authors with revisions. However, Tyndall did receive feedback on the paper through another channel: personal correspondence from Stokes.

Tyndall and Stokes

Stokes and Tyndall had known each other since the early 1850s. The two Irishmen likely met for the first time at a gathering of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and their shared interest in physics led to a lifelong professional relationship.

In a letter dated 7 May 1861, Stokes informed Tyndall that “your paper was ordered to be printed last Thursday.” He told the author that he had been one of the referees, and he suggested five places where he thought Tyndall should clarify or reconsider his arguments. Some of the suggestions were minor. For example, Stokes rightly pointed out that heat could be lost to the rock salt in Tyndall’s experimental setup.

Stokes’s most significant comment was about Tyndall’s discussion of the relationship between conduction and radiation, the issue Stokes had mentioned to Thomson. Tyndall suggested that good conductors were, as a rule, bad radiators, and vice versa. Stokes told Tyndall that he did not believe it was necessarily a “physical law” that good conductors had to be bad radiators:

“You suppose that in the case of a good radiator a molecule does not lose much motion by communication to the adjacent molecules because it has already lost it by communication to the ether... But it seems to me that the loss by communication to the ether and the loss by communication to other molecules must take place sensibly independently of each other.”

Tyndall’s published paper reflected changes in response to all five of Stokes’s suggestions. Most noticeably, Tyndall softened his conclusions about conduction and radiation and cast his work as an invitation to further experiments rather than a solution to the puzzle:

“Why should good conductors be, in general, bad radiators, and bad conductors good radiators? These, and other questions, referring to facts more or less established, have still to receive their complete answers.”

In making the changes, Tyndall does not seem to have been merely bowing to pressure from a powerful editor. In fact, he and Stokes exchanged several further letters about the paper. Stokes, who served as the society’s physical sciences secretary for more than 30 years, often suggested changes to authors via personal correspondence. Tyndall sought and received clarification on several of Stokes’s criticisms. He clearly valued Stokes’s judgment and took his ideas seriously. In one letter, Tyndall told Stokes that he did not feel coerced to change his paper. Rather, “any point on which you have thought, and regarding which you have arrived at an opinion opposite to mine, demands from me very careful consideration before committing myself to print upon the subject.”

To sum up, with such an elegant and gentleman peer-review process, how did we reach to the current state of the Science today? I’ll hopefully try to explain that on the following post.

Buena pregunta final para un buen post!. Esperando la continuación.