The Tokenization of Sky for Drones and Air Taxis

Why Ownership — Not Engineering — Will Decide the Future of Airspace

Commercial drone delivery is no longer experimental. It is becoming digital infrastructure, with the United States leading and the UK and Ireland close behind.

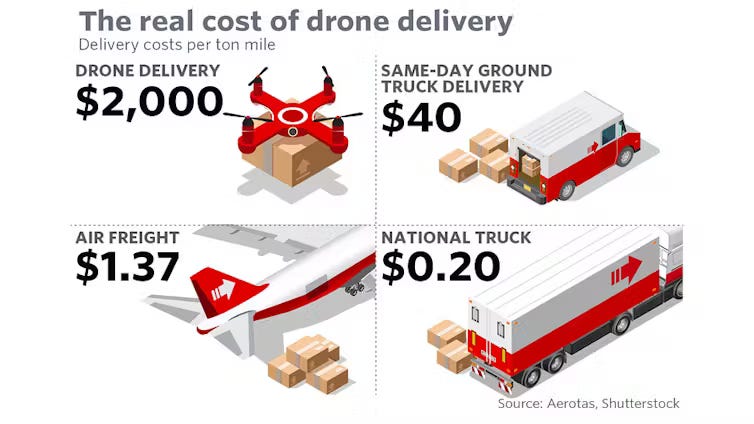

The thesis is simple. They say that drone delivery is faster, cleaner, and cheaper than trucks. I’m not so convinced about that, but as I’ve sometimes proved all the statistics can be manipulated so that you choose the winner ones for you. It’s not the same to take into account the pollution per delivered package, or per delivered mile, or per delivered euro unit…

But the real story isn't about drones. It's about airspace. Who controls it, who profits from it, and whether this infrastructure will be built through markets or command and control seizure. And in this post, I’m going to talk about air rights.

What are Air Rights?

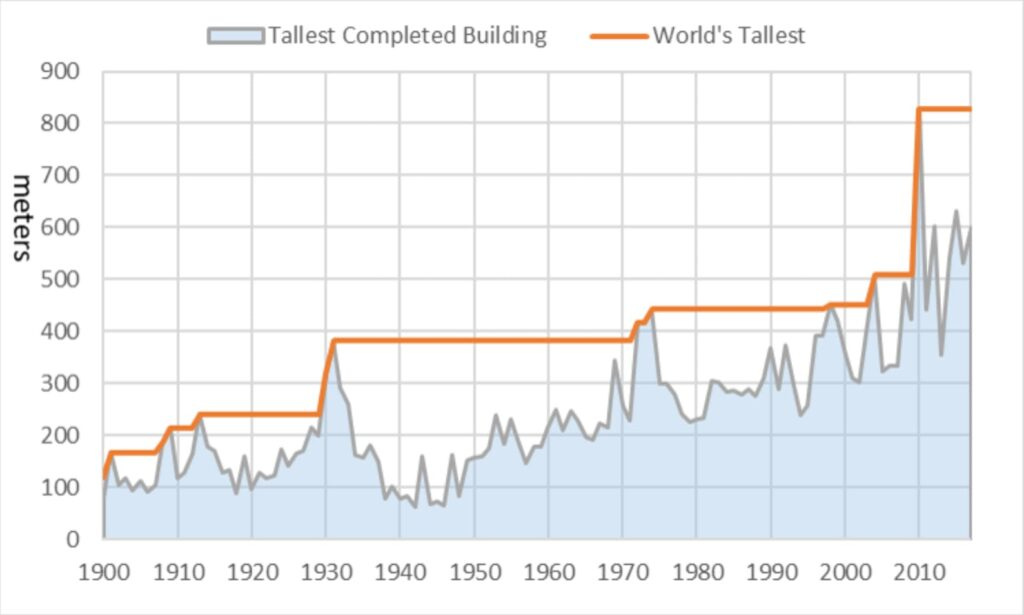

In the 1950s, there were only 160 skyscrapers in the world, with half of them located in New York City. On average, these buildings stood about 570 feet tall.

Seventy years later, things look very different. In 2020 alone, 106 new skyscrapers were constructed, and the average height of these modern towers has doubled to around 1,300 feet.

Skyscrapers keep getting taller. A cool thing about this graph is that it also looks like a skyline.

But there was a problem.

The spaces directly above, below and adjacent to skyscrapers were getting extremely crowded. Citizens and governments became concerned. Even developers realized that building on top of this massive infrastructure had become a tall order (sorry).

With that, the concept of air rights was born.

Air rights are the legal right to construct (or prevent construction on) the vertical air space directly above a plot of real estate.

This is a new concept. 100 years ago, it didn’t exist. In fact, ancient law from the Romans dictated: Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos.

This translates to, “Whoever owns the soil, it is theirs up to Heaven and down to Hell.” Which basically means that if you owned property, you could build as high above it (or as low beneath it) as you pleased.

Now, air rights are a force multiplier. They are now a recognized asset class, with a global value in the trillions of dollars. They support development, help release hidden value, and allow cities to grow denser without pushing people out. They also make it possible for airports to manage takeoffs and landings through privately held air rights beyond the airport’s own borders. In such cases, airports pay the air rights owners for access. From Manhattan to Texas, and from London to Sydney, these rights have been used to finance housing, infrastructure, and overall economic progress.

Recent transactions show clearly how valuable this type of asset has become. In West Harlem, a 28-story building was made possible by a $28 million deal for air rights above a parking lot. The money went toward repairs for 3,000 residents and helped create 147 apartments for middle-income families.

In Midtown, an office building was bought for $38 million — not mainly for the structure itself, but for the 15,000 square feet of unused vertical air rights that came with it. On Broadway, a three-story landmarked building was sold for $13 million. Its true value was not the old cafeteria inside, but the 23,000 square feet of unused air space above it.

These are not anecdotes — they are signals. Air rights are not theoretical; they are a real, monetizable asset. And they are no longer only about towers. The same market logic now applies to low-altitude logistics.

The future of drone delivery is not driven by battery technology, but by ownership. Who controls the air above your property? The answer shapes whether our economy remains consent-based or becomes coercive.

Above us, where policy, property, and national security overlap, the fight for American airspace has begun. What started as a reaction to foreign drones and rogue balloons may redefine ownership itself.

Control, Not Charity

Drone companies routinely avoid the most important question in logistics. Who owns the air over your home?

In the United States, UK, Ireland, Canada, Australia, and others the answer is clear. Landowners control the immediate reaches of their airspace, generally up to 500 feet. The US Supreme Court confirmed this in United States v. Causby. Intruding into that space without consent is trespass, and potentially an unconstitutional taking.

Some drone companies tried to bypass local control by pushing for federal authority. It didn’t work. Others fly without consent — that’s not scalability, it’s legal risk.

When a company or government uses your land or airspace without compensation, it’s not innovation — it’s taking.

There’s a better approach. States and cities can lease airspace above public roads to create drone corridors. Private landowners can choose to join, and if they do, they get paid.

This is how low-altitude logistics should function: as a market, not a mandate. Flights are priced by the mile, with income going to homeowners, and local governments. This model reduces conflict, lowers legal risk, and brings new revenue to communities. If drones fly over your property, you should be compensated — just like with mineral rights.

Costs, costs and costs

Drone delivery is already active. Zipline has made over 1.4 million deliveries and flown 100 million autonomous miles. In Ireland, Manna runs 300+ daily deliveries, targeting 2 million a year. Walmart has completed 400,000 deliveries across six U.S. states, while Amazon and Wing are operating in Texas, Georgia, and California.

Investment is following. The drone industry draws billions annually, with the U.S. receiving over 50% of global funding — thanks to its scale, infrastructure, and legal system rooted in private property rights.

Most deliveries fit the model: 70% of Walmart packages and 85% of Amazon packages weigh under 5 lbs. 90% of Americans live within 10 miles of a Walmart. Drones can deliver in 3–30 minutes and emit 94% less carbon than cars.

Initially, drone delivery was a premium service, costing $9–$15. With scale, autonomy, and BVLOS approvals, costs fall under $5. In ideal conditions with airspace access, they can drop below $2.50.

Trying to use private airspace without consent leads to lawsuits and public pushback. With permission, those risks disappear — and margins increase.

The main challenge now is economic viability. Early Walmart DroneUp tests cost up to $30 per drop due to labor. McKinsey estimates $13.50 per delivery without BVLOS. But with fleet autonomy and one operator for 20 drones, costs drop to $2. A recent U.S. executive order accelerates these approvals.

In the UK and Ireland, companies already operate at this level — 20 drones per pilot, 80 deliveries per drone daily. With air rights included, they reach break-even around $2 per order. In low-density areas, it’s already cheaper than ground delivery.

We’ll see.

So you're agree with tokenizing everything until life itself will be tokenized? 😅

This is crazy, this system is sick and will lead us to an ever-worsening dystopia...🤬🤦🏻♂️😏