Nonlinearity of technological unemployment

No regulation was needed: Amazon recognized their failure in cashierless supermarkets.

In 1963, the black working-class revolutionist James Boggs wrote in his book The American Revolution of a coming cataclysm in American industrial production. As an autoworker at Chrysler in Detroit, Boggs had an intimate knowledge of the changes introduced on top factories. He saw one particular harbinger of this coming utter devastation of the working class: automation.

The contemporary usage of the word automation has its origins in the Automation Department at Ford Motor Company set up by vice president of manufacturing Delmar Harder in 1947—even though Harder’s actual proposals for the reorganization of work in Ford’s factories primarily relied on XIX century technologies designed simply to speed up the production line. By the early 1960s when Boggs wrote of this fast-approaching wave of automation, the term had come to mean the replacement of jobs once done by human laborers, by machines. Central to Boggs’s analysis of automation is his insistence that the process will create a massive surplus population of “outsiders,” people whose labor has been made superfluous and obsolete who cannot get any other job.

Most of the technologies involved in automation had been developed and implemented in other industries years before their incorporation into Ford’s production process. What made this technology new was its centrality to Ford’s manufacturing strategy, coming at a time of historic unrest among autoworkers, and in particular, on the heels of a costly twenty-four-day strike at Ford’s massive River Rouge plant in May of 1949.

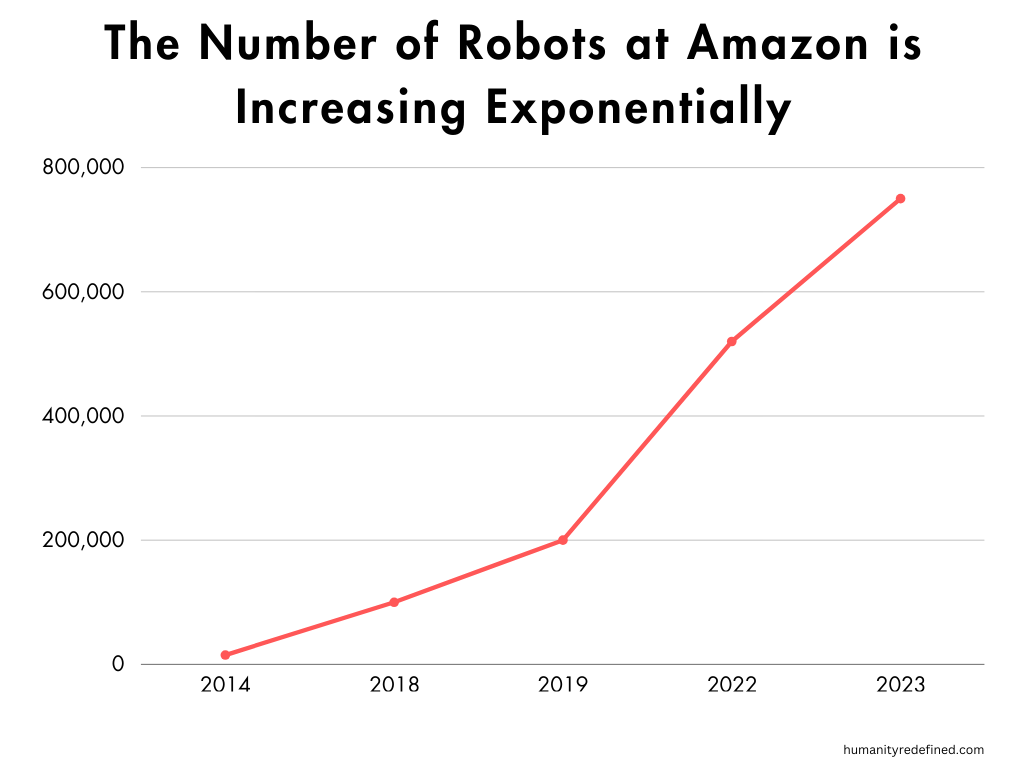

This week, I read that Amazon plans to automate more its warehouses as a response to the labour shortage and high turnover. Take a look at their efficiency. According to the evolution in their number shown in the next picture, I would be surprised if by 2025 they do not reach one million robots. Similar threat was made by McDonald’s long ago. That time, 15$/h was the signal to unleash the robot revolution.

Now, these years, we keep having a carrousel of news about robots replacing humans. This week, a loudly advertised study by MIT told us not to worry:

People are worried that AI will take everyone’s jobs. We’ve been here before.

In a 1938 article, MIT’s president argued that technical progress didn’t mean fewer jobs. He’s still right.

It is inevitable to express an opinion on this debate without being tainted by ideology and I cannot take very seriously this kind of studies. Sorry. I sometimes feel that making such economic and technological predictions is as stupid as considering that our lives are linear. Sorry again, they’re not, they’re high order chaotic systems, and thus, I think that researchers who finely predict technological future will be a result of the infinite monkey theorem.

My only view is that in the famous report Why are there are still so many jobs? (2014)

Automation, complemented in recent decades by the exponentially increasing power of information technology, has driven changes in productivity that have disrupted labor markets. This essay has emphasized that jobs are made up of many tasks and that while automation and computerization can substitute for some of them, understanding the interaction between technology and employment requires thinking about more than just substitution. It requires thinking about the range of tasks involved in jobs, and how human labor can often complement new technology. It also requires thinking about price and income elasticities for different kinds of output, and about labor supply responses.

People would like to know short and binary answers, but people themselves will build these answers as we evolute as society. I suspect that some countries would receive the replacement of human cashiers in supermarkets by machines, than others. I think that socially people would accept. Again, the giant of eccomerce: Amazon recognized the bad idea of their cashierless supermarkets, and the selfcheckout machines are considered now a failed experiment.

What about robots in restaurants? There’s a real shortage of labour in that field, fewer people want to work there, and luckily, their salary conditions are increasing. In addition to that, raw materials, taxes and logistics are increasing. Probably restaurants and cafeterias will have to keep increasing their prices in order to fufill with all these issues. Would be ready to pay 3€ for a cup of coffee, when needed? Or would we prefer a robotic service that helps the business reduce the costs, and help reducing the price of our drink?

Post-scarcity is a theoretical economic situation in which most goods can be produced in great abundance with minimal human labor needed, so that they become available to all very cheaply or even freely. Karl Marx argued that the transition to a post-capitalist society combined with advances in automation would allow for significant reductions in labor needed to produce necessary goods, eventually reaching a point where all people would have significant amounts of leisure time to pursue science, the arts, and creative activities; a state some commentators later labeled as "post-scarcity".

Let me clarify that I’m against any communist regime of work. However, maybe the question is not to continuously research how many jobs are in danger of automation, but what if less and less human workers are needed, and how could society benefit and evolve for a better situation. Maybe alternative frameworks to what is all work about are needed.

NIce post, Julian

Very good post, Julián. Automation is probably the main cause of the growth of job insecurity from the 1980s onwards, and not so much the process of relocation of globalization, nor the reduction of the role of unions, nor social atomization. Generative AI represents a new turn of the screw, this time perhaps aimed at reducing white-collar jobs and not so much blue-collar jobs.

Personally, a question that makes me think is how we are going to socially adapt to a new scenario in which, not so many new jobs may be generated as those that are destroyed. Because some cultures, such as the Anglo-Saxon, have a powerful vision of the meaning of life centered on work, and will be really challenged. Latin cultures are more oriented toward enjoying life and amalgamating the meaning of our lives around that social relationship which seems to remain more. We'll see.